|

I witnessed "Hail We Now Sing Joy" at the Milwaukee Art Museum during the Members Only opening on Thursday. I also witnessed Johnson's accompanying artist talk. Johnson is interested in, as he put it, "cultivating witnesses." Witnesses can tell the story of the art object. Witnesses make experiences into history.

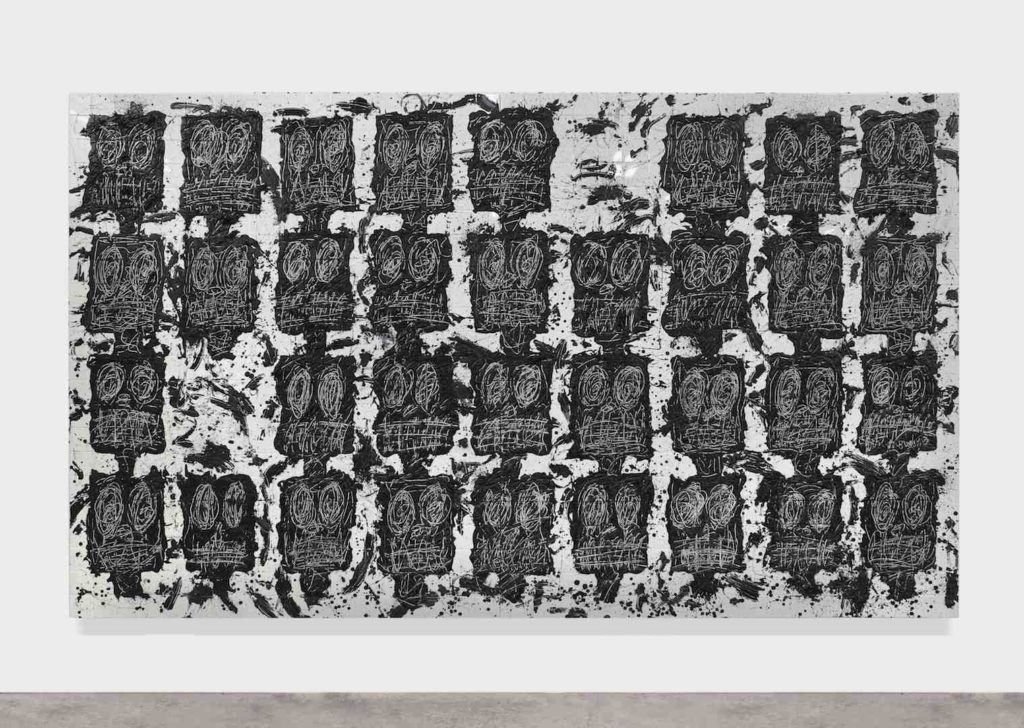

I witnessed Antione's Organ, a giant installation of plants in Johnson's handmade pots (accompanied by bugs and dirt), books (Wright's Native Son, Beatty's The Sellout, Coates' Between the World and Me, and Dickerson's The End of Blackness), fluorescent grow lights, boxes of African shea butter, sculpted shea butter, and small tvs playing short films (one of Johnson applying shea butter, another of a woman from a gospel choir, another of Johnson watching Coates on TV). These objects live in a black grid structure, all activated from within by a secret piano player. After experiencing Antione's Organ for a few minutes I became aware of how others were interacting with the installation. The majority of the large crowd stood a significant distance from Antione's Organ. The installation is very tall, so perhaps they stepped back to take in the entire piece, but I suspect most people didn't know how to interact with it. Great art makes viewers (witnesses?) uncomfortable and Antione's Organ had the contradictory effect of making people feel both unease and peace. This sense of peace, or perhaps wholeness, pushes toward another of Johnson's objectives: healing. Johnson's Anxious Audience paintings filled the walls of the exhibition's largest room, giving the witness the feeling of being on stage, a silent drama where the actors and audience stare at each other and then look away. Hundreds of witnesses fill this room and the work sharply contrasts the show title, Hail We Now Sing Joy. I felt troubled as I sat on a comfortable black bench in the middle of the room. The gaps in the work, the unoccupied spaces, made me sad. Why weren't they here with us? At the back of the gallery is a separate reading room that includes multiple copies of the books in Antione's Organ, along with some comfy seating. A handful of people browsed the books, another handful read intently despite the bustling opening: witnesses. The curation of the show is standard. The work is grouped by series: Antione's organ in the first room, Escape Collages in another, Falling Men in another, Anxious Audience in another, and the reading room in the back. I can't help but wonder how a single room of work would change my experience. Instead of progressing from relative calm to significant distress, what sort of emotional cacophony would I witness? Gregg Bordowitz asked me (as I'm sure he has asked Johnson and hundreds more of those he teaches), where does the emotion lie? in the artist? the artwork? the viewer? My answer is in the experience of the work. It is at the level of experience that the viewer witnesses the work. (John Dewey pronounced so much with his seminal text Art as Experience.) Now, I think art objects can be witnesses as well. Perhaps Johnson would agree.

0 Comments

Amy Feldman. Heavy Vector. 2013. Acrylic on canvas. 80 × 80 in. You missed it. But, I didn't. Riot Grrrls was an important counterweight to the overwhelming Takashi Murakami retrospective. Featuring 10 feminist, punk painters, the show stands in clear opposition to Murakami's work and words, carving out an important space for feminist voices. Each artist, with an interest in visual and written language, engages in an act of refusal: refusal of imagery, beauty, convention, or history.

The show also works together because of the artists' hyperawareness of edges. As Edward S. Casey notes in "The Edge(s) of Landscape: A Study in Liminology," "The power is in the edge." Having awareness and control over edges is an act of political agency and power. Amy Feldman exercises this control in Heavy Vector, boldly asserting her mark-making in steel-gray on white. Attacking the canvas, Feldman mobilizes edges; they are where the action happens, where the power resides, where forces collide. Similarly, Judy Ledgerwood's Sailors See Green is a conglomeration of edges that recall textile patterns while showing evidence of Ledgerwood's hand and establishing a relationship between Ledgerwood's body and the the superhuman-sized canvas. The best moment of this painting, however, is a subtle edge. (Casey defines this as an edge that is "ambiguous in its appearance.... We cannot track, much less name or number the transition from one to the other.") This moment is at the top of the canvas. Is the canvas warped? Sagging? Where does the canvas end and the wall begin? The canvas appears to be unstretched, yet the other edges clearly tell the viewer that canvas is rigid. Molly Zuckerman Hartung's Hedda Gabbler is a frenzied externalization of Hedda's inner world. Zuckerman Hartung respects the picture plane around three edges, but advances, penetrates, the edge on the fourth side allowing her marks to meet and presumably escape the edge, just as Hedda escapes the power of Brack (through suicide) at the end of Ibsen's play. Mary Heilmann has mastery over the edge in Metropolitan, laying out two grids, one on top of the other. The irregularity of the edges of the stairs provides visual interest in an all-over Pollock-like way, yet refuses the apparent happenstance of Pollock's compositions as well as the precision of tile flooring. Heilmann's red lines form a more precise grid, meticulously taped. However, Heilmann is unselfconsious about the moments where the background bleeds under the tape. In this way she asserts her own subjectivity. The curation of Riot Grrrls is strong, but Ree Morton's One of the Beaux Paintings (#4) is out of place visually. Hanging Feldman's Heavy Vector alongside Ledgerwood's Sailors See Green creates a strong visual presence and opens up a conversation between two works from 2013. This strong wall, however, unfortunately cancels out Jackie Saccoccio's Portrait (Stubborn) from the same year on the adjacent wall. The exhibitions wall labels are disappointing (they almost always are), especially the text for Ellen Berkenblit's Love Letter to a Violet which states, "A female face in profile dominates this work, expanding beyond the confines of the canvas. Ellen Berkenblit includes stereotypically “girly” details: thick eyelashes, a hair clip. Step closer to the surface and the confident, assertive lines she uses to depict these elements also become part of an abstract composition. Interlocking planes of punchy colors run through both figure and background, keeping the eye in vigorous motion." The directive to "step closer" to the surface is a clear power play that assumes the viewer cannot see the work properly on her own. The rest of the text introduces the notion of strong figuration in the work which sacrifices the opportunity to let abstract possibilities play in the viewer's mind. The use of "girly" in quotes leads to many questions, especially because the next sentence discusses Berkenblit's "confident, assertive lines." Overall, Riot Grrrls delivered just like the feminist punk scene with all its accompanying messages and art forms. Participating Artists: Tomma Abts (German, b. 1967) Ellen Berkenblit (American, b. 1958) Amy Feldman (American, b. 1981) Mary Heilmann (American, b. 1940) Judy Ledgerwood (American, b. 1959) Ree Morton (American, 1936–1977) Joyce Pensato (American, b. 1941) Jackie Saccoccio (American-Italian, b. 1963) Charline von Heyl (German, b. 1960) Molly Zuckerman-Hartung (American, b. 1975) |

3rdCoast4thWaveAuthorKate E. Schaffer: artist, writer, weirdo. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed